Project Zomboid Is The Only Zombie Game That Actually Understands the Apocalypse

There are a lot of zombie games on the market. Everyone knows about Left 4 Dead, Resident Evil, and The Last of Us. Most are aware of World War Z or Dying Light, and even casual players have probably dabbled in Call of Duty’s Zombies mode at some point. The genre isn’t niche — it’s one of gaming’s most crowded spaces. But while many of these titles focus on action, spectacle, or cinematic storytelling, not many attempt to simulate what surviving the apocalypse would actually feel like. That’s where Project Zomboid comes in.

Unless you’re into indie games, you may not have heard of it. Like RimWorld or Terraria, it’s a cult classic that debuted on Steam over a decade ago. Despite consistently maintaining five-figure player counts in Early Access and boasting a massive modding scene, it remains obscure compared to the giants of the genre. Which is a shame, because when it comes to capturing the reality of a zombie apocalypse, nothing else comes close.

Like any good title that focuses on an unrealistic apocalypse, Zomboid’s premise is almost comically simple. You’re thrown into an open world map the size of an actual state in the Southern US, and told to survive until you can’t anymore. There are no quests in the title, no narrative, and only recently did it add a tutorial. Every time you begin a run, it starts with the same message: this is how you died, as a track reminiscent of 28 Weeks Later swells in the background. The only equipment you begin with are the clothes on your back and whatever items you can find in your randomised starting home. Everything you do after you leave that respite is entirely up to you, and will almost certainly result in your death sooner rather than later.

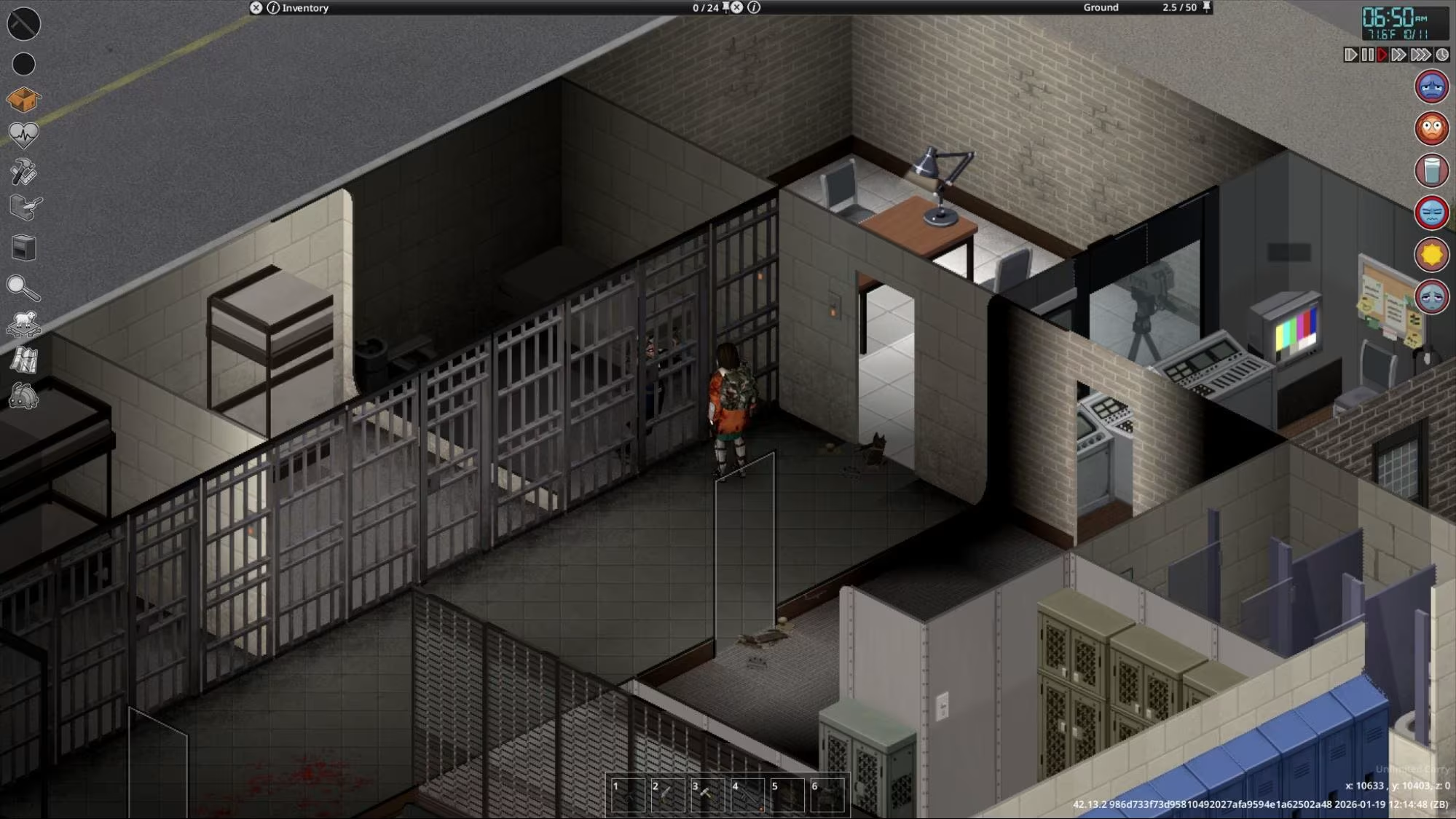

Project Zomboid is great for two reasons. The first, and most important, is that it’s an actual survival game. A lot of titles require your character to eat and drink regularly. Some, like SCUM, have more nuanced health mechanics. Zomboid takes it a few steps further, though. It’s the only zombie game that treats survival like a systems problem instead of a power fantasy. The in-game day to in-game day gameplay isn’t all that special. The title uses an isometric camera angle, à la the recent I Hate This Place, which makes it surprisingly easy to deal with small groups of zomboids, provided you have the right equipment. Its world is also filled with lootable canned goods and soda that will keep your character alive.

Just like in real life, though, you can’t subsist solely off of unlicensed pop and microwavable meals in Zomboid. Doing so will make your character sick, and if that illness goes untreated, you’ll die in the most mundane way imaginable. So you have to cook real meals in the game. That means you’ll have to do loot runs. The places with the best supplies are often occupied by hordes, however — and like in real life, you can’t swing a hammer or shoot a gun until they’re all re-dead. Your character will get tired and develop muscle strains that require you to rest for actual hours. If, or when, you get scratched by a zombie, you’ll also have to treat it realistically. You need to keep your wounds clean and disinfect them if you don’t want to join the ranks of the creatures trying to kill you. You can don protective clothing that’s either crafted or found in the world, but that too has downsides. If your character sweats too much, you’ll need to direct them to a shower. If you fight too big of a horde, they’ll get nervous, which you can treat with alcohol and cigarettes that each come with their own problems. Playing Zomboid is, in effect, like living out a day in your actual life if you didn’t have a job and everyone on the planet wanted to kill you.

Project Zomboid is far and away one of the most realistic games on the market. That’s not the only string to its bow, though. The other is its giant world. Lots of developers love to tout how big their maps are, but Zomboid puts them all to shame. It isn’t the biggest if you’re only accounting for square mileage. However, you can enter literally every room and building in the title, of which there are thousands. Its Bateman Office Building, for example, is a 28-storey skyscraper filled with hundreds of rooms you can clear or set up a base in. It’s located in a detailed depiction of Louisville, Kentucky. That city has scores of similarly complex structures, each one of which contains anywhere from dozens to thousands of the undead you need to kill. And that’s only one corner of a map that feels less like a level and more like an abandoned state.

Exploring these is enjoyable, and not just because of the novelty of it. Zomboid, at least when played in single-player, makes you actually feel like the last man (or woman) on Earth. It’s cool to see the details of places you could never visit in the real world. Whether that’s a military base, prison, giant hospital, or even a mansion, it never gets boring. The trek you need to take to get there is similarly an adventure, just like going on a road trip. And you always have a reason to do that because of Zomboid’s mechanics. You won’t find antibiotics or assault rifles laying around in any of the game’s starting towns. But, depending on how you play, you’ll need them eventually. You’ll also have to look both near and far for crafting materials that let you fortify your base, and parts for whatever vehicle you end up using.

All of this means that Zomboid is simultaneously one of the only titles that’ll let you see how you’d fare in the apocalypse, and a true “water cooler” game. Everyone who plays it will have a wildly different experience. You can mess around with mods, multi-player or world settings to drastically change how it plays. However, even in vanilla Zomboid, no two runs will ever be identical. You may die in your well-stocked base after an in-game year because your alcoholic character ran out of booze. Or you could perish when you forget to put on shoes and then walk over broken glass. Stories like that were the best parts of the World War Z book, or the early seasons of The Walking Dead. Everyone knows that nobody truly survives the end of the world, it’s just a matter of how the survivors eventually perish. That’s not something any other game in the genre showcases, though. Those titles, for as good as they often are, aren’t realistic and seldom let players generate their own stories. Zomboid isn’t a game for everyone. It’s slow, punishing, and often brutally mundane. But it’s also the only zombie game that truly understands what the apocalypse would be: not a power fantasy, not a heroic last stand, but a gradual, inevitable decline. Most zombie games let you win. Project Zomboid reminds you that you were never supposed to.

You can subscribe to Jump Chat Roll on your favourite podcast players including:

Let us know in the comments if you enjoyed this podcast, and if there are any topics you'd like to hear us tackle in future episodes!